The Mississippi School Bus Crash

Published on Oct. 31, 2011

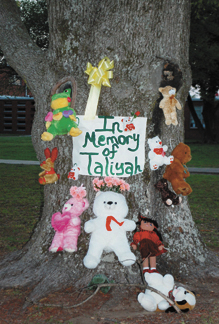

Taliyah McRoy, a 10-year-old with plans to become a teacher some day, was a ball of energy. She loved dancing, riding bikes, playing, getting good grades at her elementary school and being around her family and friends, according to her cousin, Jasmine McRoy.

On April 1, 2011, Taliyah was fatally injured when her school bus smashed into an 18-wheeler at a highway intersection. She reportedly died moments after her mother arrived at the crash scene in Shaw, Miss. All 15 children in the bus were injured, according to Sgt. Ben Williams of the Greenwood District of the Mississippi Highway Patrol.

Taliyah McRoy died in the second fatal school bus crash in Mississippi this year.

In February, a truck driver and two teachers were killed and 10 students were injured when a tractor-trailer crashed into two school buses near Oxford, according to the Mississippi Highway Patrol.

The school buses in the two fatal crashes were not equipped with lap-shoulder safety restraints – more commonly known as seat belts. Although the federal government mandates seat belts in passenger cars, it lets states decide regulations for the buses that transport most of the nation’s children to school. And most states, like Mississippi, do not require seat belts in most school buses.

It’s not known whether Taliyah McRoy or the two teachers would be alive today if she had worn a simple seat belt.

But the deadly Mississippi school bus crashes shine a spotlight on an emotional four-decade national debate that pits safety advocates and the medical community against federal and state regulatory agencies. In a nutshell, most government agencies say seat belts in school buses are not necessary, that school buses are already very safe. But safety advocates say penny-pinched lawmakers are sacrificing the safety of children to keep costs down.

‘Embarrassingly Minimal’

In March, Ronald Medford, deputy administrator of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, underscored the necessity of seat belts in commercial passenger buses. He told a Senate transportation subcommittee that NHTSA would initiate a rulemaking process to require seat belts in new commercial passenger motor coaches in order to ensure passenger safety.

But in late August, NHTSA, the same agency that wants to require seat belts in new passenger buses, refused to require seat belts in most new school buses.

The agency denied a petition by the Center for Auto Safety, a non-profit founded in 1970 by The Consumer’s Union and consumer advocate Ralph Nader, to write a rule requiring seat belts in large school buses (over 10,000 pounds) that transport most of the nation’s 50 million kids to school.

The Center for Auto Safety petition was signed by a representative of the American Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Orthopaedic Trauma Association as well as a number of consumer and child advocacy groups that were dissatisfied with a 2008 NHTSA rule that required seat belts only on new small school buses. That rule did not mandate seat belts on larger school buses, over 10,000 pounds, which transport most students.

“The laws of physics are not repealed because one bus is longer than another,” the Center for Auto Safety wrote. The center contended that NHTSA’s efforts to protect children riding school buses are “embarrassingly minimal.”

But NHTSA, the National Association of Pupil Transportation and the National Safety Council all argue that seat belts on school buses would not make a significant difference in child safety.

“We’re asking agencies to invest billions to put in a safety device that would not have a significant impact for the amount of money, time, effort and resources used,” said Ulcyzki of the National Safety Council.

NHTSA, in its denial of the petition, said it “has not found a safety problem supporting a federal requirement for lap/shoulder belts on large school buses, which are already very safe. “

The agency estimated the cost of installing lap/shoulder belts in large school buses at $5,485-$7,346. That translates to a cost of between $23 and $36 million per life saved, the agency wrote in its denial of the Center for Auto Safety petition.

NHTSA left the decision to install seat belts on most school buses to state and local jurisdictions, most of which have elected to forego the added protection.

School Bus Death Count

Local officials argue that school buses are among the safest forms of transportation in the country and that installing seat belts is too expensive for the “statistical life” that would be saved. But safety experts counter that even one child’s death caused by lack of a seat belt is too many.

And children do die in school bus crashes.

In its denial of the Center for Auto Safety petition seeking federally mandated seat belts in school buses, NHTSA estimated that each year, about 19 kids die in school bus crashes. Of these victims, only five are actually in the bus, NHTSA reported; the other victims are pedestrians near the bus.

However, the number of child deaths might be larger. School bus crash data does not include statistics from extra-curricular field trips, said John Ulcyzki, group vice president of the National Safety Council. The omission of such data might cause the official count of fatalities and injuries to be lower than the actual count, although Ulcyzki said he believes there isn’t much of a difference.

Many more school bus passengers sustain injuries in crashes. In a 2002 School Bus Crashworthiness Report, NHTSA reported an average of 26,000 school bus crashes annually between 1991 and 2002. The report, the most recent available, also stated that “American students are nearly eight times safer riding in a school bus than with their own parents and guardians in cars.”

Compartmentalization

In 1967, the University of California at Los Angeles conducted a study that concluded compartmentalization should be the first step toward safety school buses. The second priority, the study said, should be seat belts.

More than 40 years later, only seven states – New York, New Jersey, Florida, California, Louisiana, Texas and Connecticut – have school bus seat belt laws on the books. But state laws often contain loopholes that allow school districts to avoid installing seat belts on all buses if they choose.

States that do not mandate seat belts in school buses say the vehicles are already safe because of “compartmentalization” – meaning seats that are placed closely together and designed with thick padding and high seatbacks in order to absorb the energy when passengers move forward and backward in frontal or rear collisions.

Children, the reasoning goes, are seated in “compartments” similar to a carton of eggs.

The seat design and placement is “extremely effective,” according to James Johnson, vice president of business development and corporate sales at Indiana Mills and Manufacturing Inc., which bills itself as an industry leader of design, testing and manufacturing of advanced transportation safety systems.

In No Shape to Drive

In No Shape to Drive